"Afew years ago, we had a family stay during the Grand Prix whose young daughter loved elephants,” says Cafiero Canestrelli, a concierge at the Hôtel de Paris Monte-Carlo, where rooms start at €630 per night in the low season. “When they found out that there were none at the zoo here, the father pushed us to find an elephant in another zoo and bring it here for his daughter.”

Since ‘no’ is a word he rarely uses, Canestrelli got to work ‘borrowing’ an elephant from another zoo further along the Côte d’Azur. “We transferred the animal to the zoo so the daughter could see it for an hour or so, and then it went back to its zoo the day after,” he explains. The cost for such an indulgent request amounted to pocket change for a millionaire out to please his child: “a few thousand Euros in transport fees.”

Despite Monaco and Monte-Carlo being used interchangeably, Monte-Carlo is actually just one of Monaco’s seven districts — although thanks to the Casino de Monte-Carlo, it is easily the most famous. I can see the ornate facade of the glittering gambling den in the morning light from where I am seated in the equally gilded lobby of the Hôtel de Paris. The property is Monaco’s oldest and most prestigious hotel built in Belle Époque style, around the same time as the casino, in 1864. The two are connected by a secret underground elevator beneath Casino Square, popular with more discrete high rollers.

Even on this quiet weekday in November, it is business as usual in this billionaire bubble. Soft piano keys, the soundtrack to five-star hotels around the world, fill the air and I am drinking a latté that cost €15. On the wall across from me, nymphs sculpted in plaster relief dance as if celebrating the eternal high life. A couple of floors above us is the 983-square-meter Princess Grace Suite, a duplex full of Hollywood-starlet-turned-Monaco-royalty Grace Kelly’s personal effects, starting from €60,000 a night.

Outside, a Dubai-plated monochrome Rolls-Royce Phantom is parked across from a parade of Aston Martins and Maseratis, although it’s too early in the morning for the designer boutiques that share the hotel’s exclusive address to be open. There is a manicured public garden out front, but the fresh smell of citrus fruit, the crop that formed the basis of Monaco’s industry until the 19th century, has long been replaced by the heady fragrance of wealth.

From Canestrelli’s perspective, the only thing remarkable about his elephant adventure was the timing. “In the middle ofthe Grand Prix, we have so much to do — and that particular request took a lot of time,” he laughs. “It wasn’t my best day.”

Hailing from Florence, Italy, hospitality is in 54-year-old Canestrelli’s blood. The son of a restaurant manager across the city’s fivestar establishments, including The Westin Excelsior, Canestrelli realized at a young age that he preferred the buzz of the lobby to the fine dining room. “The way that every day is a different job, every guest has a different request, I loved that,” he says.

He arrived in Monaco in 1994 as a freshfaced 24 year-old, after being put forward by one of his father’s friends for a concierge opportunity at another of the principality’s grand Belle Époque hotels. Two years later, he made the move to the Hôtel de Paris: “the best hotel in town.” Home is now Beausoleil, the French town that the streets of Monaco blur into at its northern fringes, with his wife and son. When he’s not working he is usually found far from the luxe of his workplace, either pottering in his garden or on the beach.

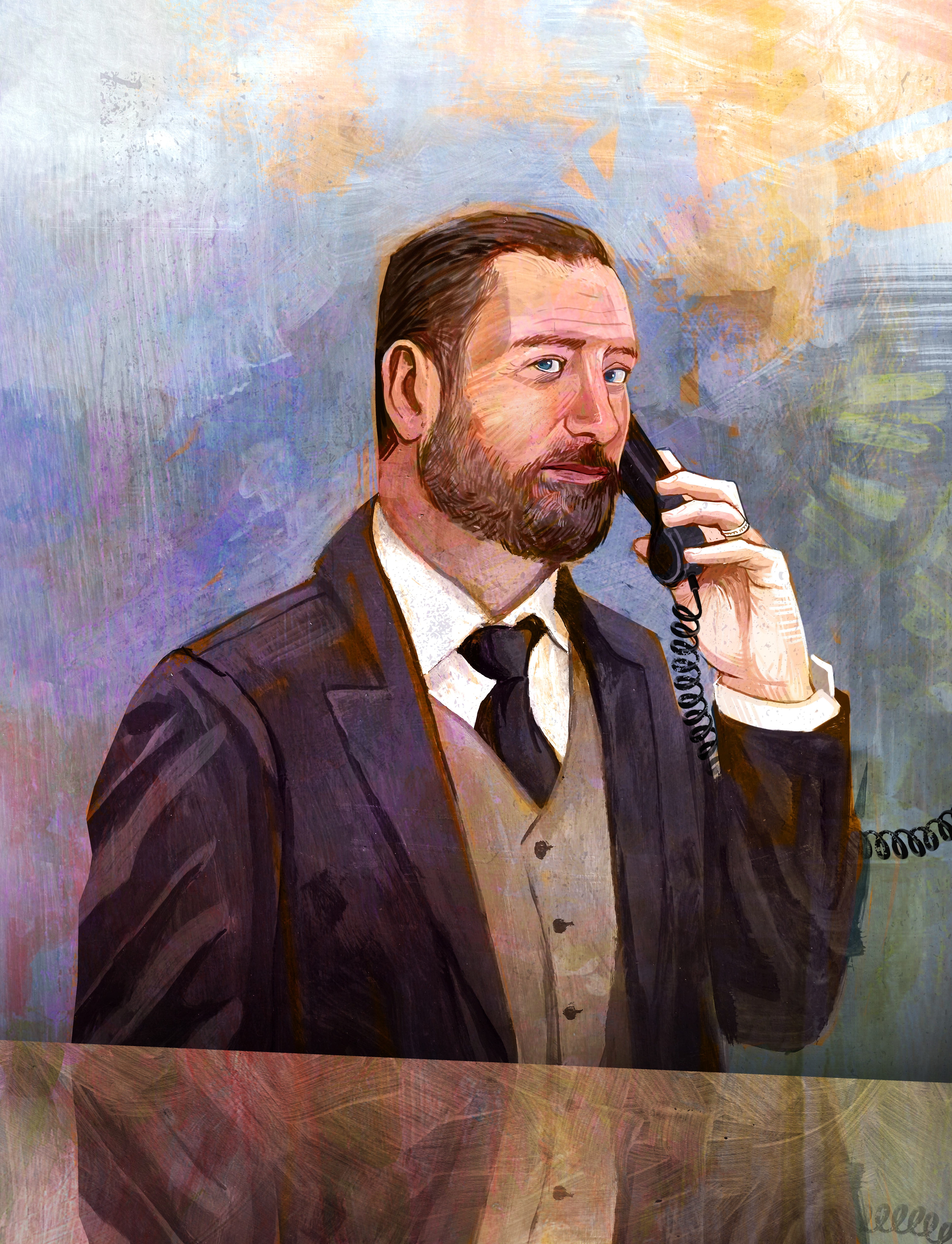

Tall and immaculately groomed, with a trim beard, bright blue eyes, and broad shoulders that fill out his navy blue tailcoat tuxedo, Canestrelli does not seem like someone who is easily ruffled. This poise is especially important during the Monaco Grand Prix, when nearly 100,000 people (triple Monaco’s population) descend on Canestrelli’s tiny principality, spending small fortunes to ensure that their weekend is flawless. As a concierge, his role is to answer any request a guest may have, from restaurant and bar recommendations to the unmentionable enquiries he deftly deflects. With 30 years of experience in Monaco, he says the level of wealth in the principality makes it the perfect place to practice his profession. He still finds a deep satisfaction in fulfilling the most difficult client requests.

Monaco is only two square kilometers in size, smaller than New York’s Central Park, so there is no escaping the Grand Prix roadshow when it rolls into town. During race weekend, the hotel’s 206 rooms can only be booked in four-night blocks, starting from €690 per room per night. Guests approach the concierge desk to ask for anything from paddock access so that they may rub shoulders with drivers, to enquiring which yachts are available for last-minute charters to watch the race, and request bookings at Jimmy’z, the quintessential Monaco nightspot on the waterfront along the Portier turn – where tables start at €5,000 over the weekend.

After all these years, Canestrelli has grown numb to the wildest of asks. “My definition of a crazy request is different to yours,” he says. “These people are so rich they can buy anything they want.” But Canestrelli ensures they can actually get their hands on what they want, right when they want it, whether that is a signed helmet and memorabilia, or a luxury watch, a supercar, or even real estate.

Canestrelli’s colleague, Matthieu Ghibo, told me about one memorable request on the scale of the elephant airlift: at the end of the 2014 race, an Azeri guest approached him for a piece of Lewis Hamilton’s car. After calling almost every contact he had in the weeks that followed, Ghibo finally secured the nose of a car Hamilton had raced in. “He was as excited as a child when we gave it to him,” Ghibo recalls.

Some of Canestrelli’s favorite drivers have stood in this lobby: Michael Schumacher, Jean Alesi, and Alain Prost. Theirs was a different era, he says. “The drivers were cool. They would say hello and happily pose for a picture.” That’s something Canestrelli feels doesn’t happen as often anymore. Of course, save for hometown hero Charles Leclerc, who comes once or twice a month for a drink at the dimly lit Le Bar Américain, the hotel’s Jazz-Age watering hole where Frank Sinatra, Édith Piaf, Cary Grant, and Charlie Chaplin once drank. “He’s very friendly,” Canestrelli smiles.

The other thing that has changed? The guests themselves. “Before, as a concierge, I was the man, because people would reserve their rooms, but didn’t know what else was going on. Guests would come to us as soon as they arrived to organize restaurants and parties,” he says. “It was busy, but it wasn’t hard work, because people were nice and smart and here to spend a lot of money for a good weekend.”

The advent of social media has completely transformed the role, though, because it has completely transformed how people interact with the Grand Prix itself. “It used to be that once someone had their room with a balcony to watch the race booked, they were happy,” Canestrelli says. Today, the actual race plays second fiddle to the flashy parties that have exploded into its orbit. “The most pressing question now is what special event people can go to over the weekend, because they want to post a picture on Instagram so everyone can see where they were and who they were with.”

The 2024 Grand Prix was the worst he has experienced. People still flash the cash, he explains, but come to Monaco much more prepared, having taken care of all their bookings and reservations in advance. “People won’t arrive without having organized their Thursday, Friday, Saturday, and Sunday nights,” he says.

Instead of being seen as knowledgeable guides, Canestrelli reflects, he and his colleagues have been morphed into troubleshooters. “A lot of people now come to us with a problem, stressed, after a quick answer,” he says. Sometimes, the interaction can verge on aggressive. He is thankful, however, for the guests who still appreciate — and respect — that a concierge service is infinitely better than Tripadvisor.

Over the years, relationships have been built up with not only the Automobile Club de Monaco, the race organizer, but also a black book of contacts who can open doors to yacht parties with Leonardo DiCaprio or Naomi Campbell. Whether people pay to get onboard usually depends on whether they are rich and famous, or just rich.

The lead-up to the Grand Prix is always hectic, but when the lights turn green on the starting grid on Port Hercules, everything stops. “Nobody calls you,” Canestrelli says. “Nobody asks for you.” It is his chance to sneak away for a quiet cigarette and coffee. But he doesn’t stray too far. The 900 meters from the start to Casino Square is reached in less than 30 seconds as drivers accelerate up Beau Rivage from the Sainte Dévote corner, taking the left-hand corner at Massenet before swinging right in front of the hotel. History has shown that some of the most memorable accidents happen here: in 2024, hotel guests had front-row seats when Sergio Pérez wrote off his car on this corner.

Sometimes guests, particularly those that have been lingering in the lobby in the hour before the race, will invite Canestrelli to come and watch the start from their rooms. That’s how he has seen first-hand a grand prix truth: “People may spend €50,000 to have a room for three days to watch a race, but 80 percent of the time, the boss is watching it on TV inside.”

By the time Canestrelli took his place behind the desk, the Hôtel de Paris had served the French Riviera’s wealthiest patrons for more than a century. “People come to us for little things, but in this kind of hotel those little things are very special things,” he says. “I love that we have the contacts that no one else has, or can resolve a problem that no one else can do, and make a difference.” See: a concierge is an expert with a satchel full of favors to cash in any and everywhere. But he also must be a magician. He can make the impossible possible, and can never show how he pulls off the magic trick. These are people used to getting what they want; they know Canestrelli is the man to ask.

Monaco transforms during race week, including the iconic Loews Hairpin.