There’s a scene in Paid in Full, the 2002 classic by Charles Stone III. Roc-A-Fella Records co-founder Dame Dash — an executive producer of the project — pulls up next to a rival Harlem drug dealer Mitch (Mekhi Phifer), compliments his fresh Saab, and immediately starts talking shit. The two hustlers engage in a game of timeless hip hop schoolyard one-upmanship: bragging about how much money they have and making fun of each other in that competitive-but-friendly cadence unique to uptown assholes. Dame ends the bullshit session by yelling from his foreign whip: “This is my Thursday car; Saturday I’m pulling up in something new!”

It was a moment that was immediately familiar to multidisciplinary artist, Dade County native, and car fetishest Mark Delmont. The 34-year-old Floridian’s output has always been influenced by work outside the fine art world, particularly rap music and film. He credits that Paid in Full scene with helping him to unlock the way cars are intrinsic to hip hop, and Black self expression. “Paid in Full was the first time I saw Black and brown people around car culture on screen,” Delmont says. “It exposed me to European cars.” Formula 1 landed in Delmont’s backyard in 2022. Now, in a new series of paintings, he examines what his native county’s car culture means, and how it fits into the international racing series, right in time for the 2025 Miami Grand Prix.

Delmont’s style is fluid, employing techniques referencing everything from anime to cubism. His recent exhibit Papers was made in this image, juxtaposing techniques in a series that spoke to the various Black communities in Miami, including diasporas from the Caribbean to South America to West Africa. Delmont is equally eclectic in his stylistic forefathers, citing influences as diverse as “Miami’s Basquiat” Purvis Young, his “O.G.” Charles Humes Jr., the graffiti artist Enrique Mas (also known as ABSTRK), and the Ecuadorian painter and sculptor Oswaldo Guayasamín. But the throughline is consistent: he’s always focused on the Black experience. “I only really paint Black and brown people,” he tells me. “That’s my thing, because we’ve been neglected in art history.”

The bearded and bespectacled painter has lived many lives. In construction, as a teen, he’d build out auto body shops around Miami with his father. He played bass and rapped under the moniker Artlovetrap. During the pandemic, he began concentrating on visual art, and found immediate success with his striking compositions animating under-explored corners of the Black American experience. But from the time he was four years old, holding on tight in the backseat while his older brother drag raced, car culture has been a constant in his life.

Delmont grew up in a house where his father owned multiple cars, often changing out rides in his collection annually (just like Dame Dash), which Delmont thought was normal. “I’d go to my friend’s house and be like, ‘Yo, y’all had this car for a long time.’ And they’d be like, ‘Nah man, that’s just your folks,’” he tells me. “So I think that sunk into my psyche. I became a car guy by default.”

He began collecting from the moment he could drive, and for a time he would buy cars from an auction, do some necessary body work, and flip them. It’s a passion and a hobby that has lived mainly in the background, outside of his work, until now.

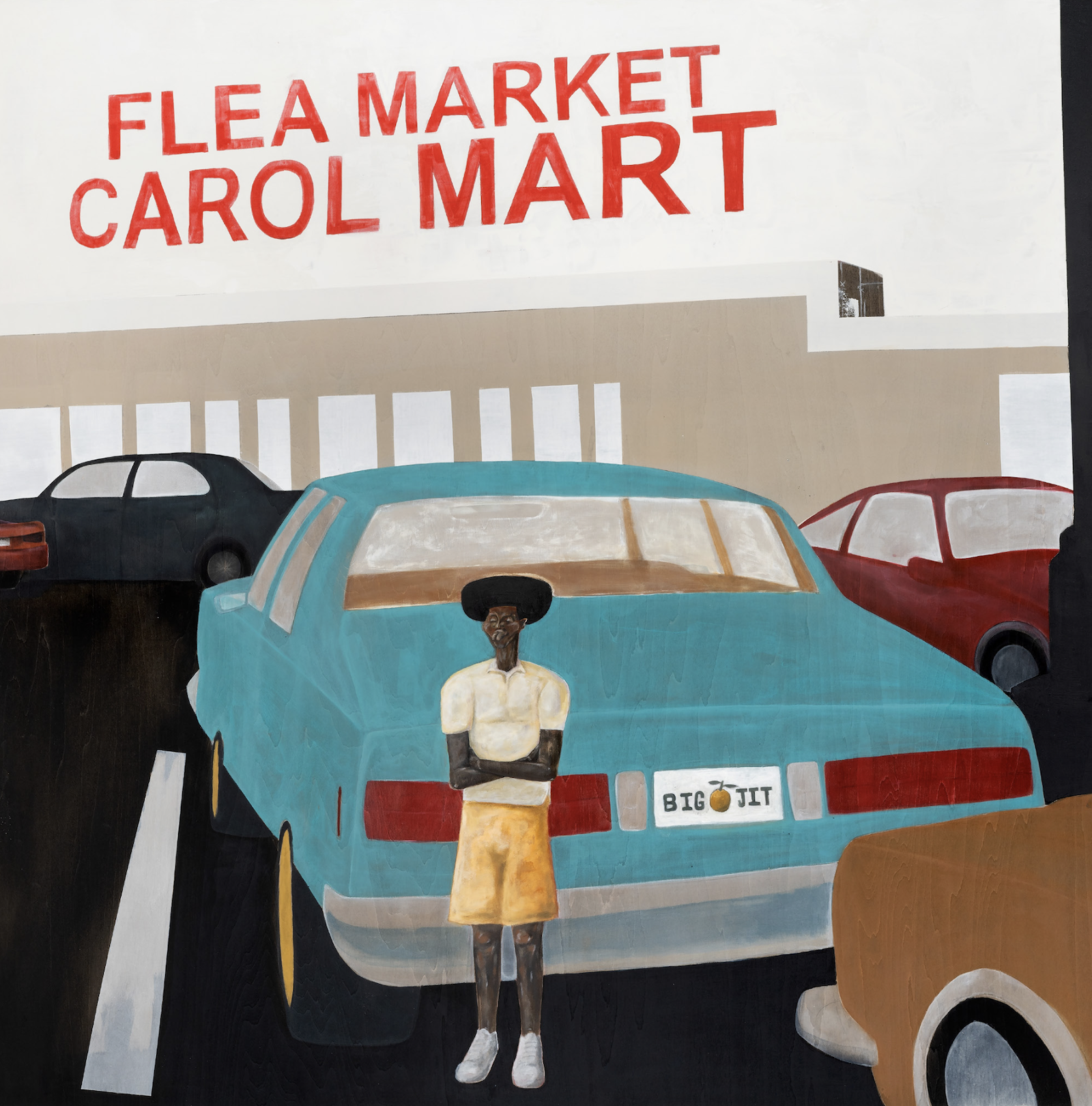

In 2022, Formula 1 held the first Miami Grand Prix around the Port of Miami, on a circuit near Hard Rock Stadium — where the Dolphins, Hurricanes, and Marlins have played off and on since 1987. The neighborhood had long been the home of a different sort of car race. “That area was always where a ton of street racing happened. You had four lanes wide on both sides. That intersection, 27th Avenue and 199th Street, was huge for Japanese cars, huge for dirt bikes,” Delmont says. “Blocks away from that, we had Car Mart, a huge flea market where people bought their rims, their sound systems, their clothes, their jewelry, and that’s where they had car shows, on 183rd and 27th Avenue.”

He sees a poetic, geographical resonance in Formula 1 choosing this hallowed ground for their race track. “I relate so many things to nature. You don’t plant a tree in dry soil. It needs to be rich, right? Carol City was rich soil for Formula 1 because the car culture was indigenous to the space.”

From the outside, it may seem like Miami is a cultural capital for fine arts, but Delmont describes a kind of flattening that comes from a market driven by tourists and snow birds: “It ends up being a lot of kitschy work. You see Art Basel and you think, ‘Damn, Miami must have like a big art scene’ but you’re going to see Marilyn Monroe, Mr. Monopoly, Pop Art pieces.” As a result, the community finds outlets elsewhere. “A lot of artistic expression comes out in lifestyle, because for a long time we didn’t have fine art,” Delmont says. “So our version of fine art was often car culture.”

“People are customizing their Japanese imports to describe their lineage,” he continues. “You seeing different flags stating where their family emigrated from hanging in the rearview, or when a friend passes away they’ll airbrush a mural of them onto the hood, or they’ll stencil their car club name onto the spoiler.”

It is difficult to even agree on the core five elements of hip hop, and writers, artists, historians, and philosophers have proposed tens, if not hundreds, of candidates for the sixth. But to Delmont, the sixth element of hip hop is clear: cars. His argument is that the art movement he describes above mirrors the approach hip hop took to music — tapping into a lamp post to power mics and turntables, rapping shit only the young Black and brown people in the South Bronx understood. Hip hop has always been a means of forging your voice, stealing and remixing found materials to create a platform. Delmont sees the same in Black car culture: take a European car made largely by non-Black people and graft Black style and sensibility onto it. “It’s self expression,” he says. “When I see these cars on the road, they look like installations to me.”

Self expression, the autobiographical and personal, is a big piece of Delmont’s visual work. The artist mainly works on canvases, but often incorporates materials into his work, specifically the construction materials of his past. “We’re not known for blue-collar work, but if you take a step back, a lot of us built these cities we can’t afford to live in, right? Even places like Miami. A lot of people don’t know Miami was built by Bahamians,” he says. “So I work with an eye on blue-collar workers to explain this was our labor, our bodies on the line, our health on the line.”

This is why the collaboration between Esses, Delmont, and Good Black Art around the Miami Grand Prix made sense. Delmont’s paintings provide a link between the new race being held in this neighborhood and the old ones. The art features Black people celebrating car culture in Dade, stationed around impromptu car shows held in Key Food parking lots, posted in flamboyant outfits next to their flamboyant vehicles, a European kitted-out sedan and a Formula 1 car at a light in Miami, looking across lanes and a cultural divide. Delmont finished these canvases with fiberglass and chrome, the materials he used to work with when he was flipping cars, expressing both himself and the culture he’s representing.

Delmont has mixed feelings about the money and attention the races have brought to the area. As a result of the institutional footprint of the complex expanding, there has been a crackdown on street racing, sending the drivers that used to speed up and down the four-lane corridors by the Grand Prix track to locales north of Miami. “It’s complicated, man,” he says, ruefully. “Being in those spaces that obviously don’t cater to you is hard, because their idea of inclusion is, like, Lewis Hamilton.”

But Delmont sees his work as an act of interpretation, a way to send the message both to his community and to the Grand Prix that Miami’s Black community cannot be shut out of their ancestral — and the Grand Prix’s new — home. “Me being here, making art about this,” he says, “it’s the squaring of a circle.”

“There’s a special place in my heart for these shop rags. I use them to add texture to my paintings. Every mechanic shop goes through a thousand a month. They get super dirty with oil and grease and then sent off to a company that cleans them and sanitizes them. So, essentially, every rag has had like twenty lives before you got to it, which I think speaks volumes.” — Mark Delmont

“When you see somebody of color in the racing head sock, most people don’t see it as a head sock. They mistake it for a ski mask. It’s a really cool conversation starter: you think about perception ofBlack and brown communities and how certain things have a completely different connotation in a different person’s life.” — Mark Delmont