In July 2025, Lando Norris won a rainy British Grand Prix at Silverstone, beating his teammate and championship rival Oscar Piastri by seven seconds.

One month later in Stockholm, the world’s top esports drivers took part in a virtual emulation of that same race, in the same conditions. On the final lap, Jarno Opmeer, who is three-time champion of the F1 esports series, was stuck in third: close to the leaders, but with no hope to win on pace.

Then he drove into the pit lane. Opmeer was literally cutting corners: The pit lane provided a more direct path to the finish line. This shouldn’t have worked, since entering the pits requires a reduction in speed from 320 kilometers per hour to a glacial 60 — but it was raining, and the cars out on track were running a lower top speed than they would in dry conditions. Opmeer did not run the math in his head. He just went for it.

And won by 0.008 seconds.

At home, a disbelieving Opmeer laughed, cursed, and spun in his chair, as the game’s camera cut back and forth from the gleeful Dutchman to the dead-eyed avatar in the cockpit. “The craziest move I have ever done,” Opmeer called it later.

This is not how Opmeer, who drives for Red Bull Sim Racing, usually wins races. (It wasn’t in this case, either: he was penalized two days later for behavior “against the principles of fair competition or sportsmanship.”) But it is how he streams.

His YouTube channel, which has half a million subscribers, updates every other day with attempts to extract the most entertainment possible from the official F1 video game: can he win Monaco from 19th on the grid? Can he lap the entire field? Can he weather the trolls in the chat, and taunt them right back as he takes the checkered flag?

At Silverstone, Opmeer’s move blurred the boundary between the streamer, who must entertain to survive, and the pro sim racer, who must be the best on track. The latter, Opmeer says, does not care about whether the race is interesting. For the former, being great only matters in the sense that greatness is interesting to watch. They are two different types of racers and they do not meet, unless one must be called upon to save the other.

At 25, Opmeer is about the same age as the current Formula 1 championship leaders — Norris, Piastri, Max Verstappen — but, in gaming terms, he’s ancient. “The average retirement age in esports is 25,” he says, on a Discord call between testing sessions with Red Bull. But is he thinking about retirement? “No. Not really.” And why should he? He is still winning.

The Formula 1 Sim Racing Championship, an official branch of Formula 1, has run eight championships since 2017. Opmeer has competed in six of them and won three — in 2020 with Alfa Romeo, in 2021 with Mercedes, and earlier this year with Red Bull. Opmeer won the third — the most of any driver in the series — in March, from a studio in Stockholm. The stage was divided into dark, strip-lit compartments, each team’s drivers sat beside one another in moulded cockpits and before monitors, racing at 300 kilometers per hour while never moving an inch.

The racing in esports is more dramatic but less theatrical than the real thing. Opmeer entered the final race in a three-way tie for the championship. In the final laps, with less than a second between every car on the grid, Opmeer’s championship rival crashed into him. A “desperate move,” cried the commentators: “‘Opmeer, I can’t let you go through, my friend.’ Not that they are friends, I don’t think.” Opmeer, damaged, lost one place — but managed to finish seventh, grabbing just enough points to win it all. When Opmeer crossed the finish line, he climbed out of his chair, removed his headset and gloves, and walked six paces to his trophy, which he held lightly aloft before a backdrop of projected fireworks. His winnings for the season totalled $50,000.

After the first year of the F1 esports series, Fernando Alonso was inspired to sign one of the top finishers to his brand-new esports team. “[Esports] is going to get bigger and bigger and it will grow up very quickly in the next couple of years,” Alonso predicted. Bigger than even Alonso’s team, it turned out: the next year, the series relaunched with a grid made up of each of the ten Formula 1 teams. For these teams, and for F1 itself, a lot of the value here is in branding, and in reaching a younger audience. The gains are obvious for a marketing organization like Red Bull; less so for a manufacturer like Mercedes or Ferrari, as there is nothing to build.

The series is run on the latest edition of the F1 video game, in which every team’s car is mechanically equal. So, unlike the real-world racing, where the best teams win by 30 seconds or grab podiums at every race, the margins in F1 sim racing are always razor-thin. Even in the seasons he didn’t win, Opmeer has never been far off.

But just like all the great competitors, Opmeer sees haters and doubters everywhere he turns. In his head, everyone is calling him a flop. The pinned post on his X profile, a celebration of his third championship, is an image compiling disparaging quotes from fans: Jarno has lost it, Jarno is washed, Flopmeer, Washmeer, Can’t qualify, Bottled it again, Why is he still racing! On X, Opmeer will get into it with anyone — “i am tbagging you next [Call of Duty] sesh”, he tells a commentator — in stark contrast to his Red Bull teammate, Frederik Rasmussen, who will at most repost the Red Bull account every second month.

See: Opmeer has the heart of a poster. “I love when someone shit-talks me, and I can shit-talk them back if I win the championship,” he says. “It makes it more exciting … or more motivating. I don’t think I would want it any other way.”

Opmeer's career exists as a response to negative experience. His early years were the same as most every hopeful F1 driver: he began karting at age four, supported by his family. He entered national championships at nine and did well, winning each of his first three years. As a teenager, he moved into a higher category to compete in European karting championships against future Formula 1 drivers — Lando Norris, Logan Sargeant, Mick Schumacher, Nikita Mazepin — to less spectacular results: a seventh place finish in a 2014 championship was his best showing at that level.

In 2016, he signed with MP Motorsport to compete in North European and Spanish Formula 4 events, placing second in his first year to countryman Richard Verschoor. On the basis of that result, Opmeer was signed by the Renault Academy and funded to race with MP Motorsport in Formula Renault, one of the myriad of unclearly named series that provide a pathway through Formula 3 and 2 into 1. In 2018, his second year in Formula Renault, Opmeer was dropped by MP Motorsport four races into the season.

It wasn’t, Opmeer says, a great team: the drivers were rookies who didn’t know enough to know that the setup of the car wasn’t good. “Once we realized,” he says, “it was too late for me.”

A more privileged driver might have been able to marshal their sponsors to save their seat, or quickly find another. But Opmeer had only ever had one sponsor from his karting days. Even if he could get into Formula 3, it would get harder, and more expensive, from there. Verschoor, one of the best drivers in the years Opmeer competed, is stuck in his fifth season in Formula 2. (“I’m 24,” he said, “[and] they’re acting like I’m 58.”)

So, Opmeer’s dream was over, exactly as abruptly as it had ended for hundreds of other young women and men.

It is a tough thing, probably traumatic, for a seventeen-year-old who has had that dream since they were four, whose ambition of growing up to race like Michael Schumacher was encoded at the same formative stage they learned how to name colors and articulate feelings. What is worse than being called washed? Being called washed and it being true.

For some grim reading, subscribe to Reddit’s karting community: every week, there is a new post from a teenager asking if it is too late for them to get on the track to Formula 1. “I don’t mean to crush your dreams or anything, but you gotta be realistic,” goes one typical answer. The F1 hopeful, undeterred at least for now, responds, “Anything can happen though.”

Some such measure of conviction — or self-delusion — is probably necessary to prevail in such an unfair, competitive sport. “It was very difficult for me to accept,” says Opmeer of his dropping by MP Motorsport. “Racing was pretty much my entire life. I couldn’t quite fathom being alive without doing something related to racing.”

Lucky for him, the year before, Formula 1 launched its esports series. Opmeer had developed a knack for the driving simulator in his time racing and found that in the F1 video game, with no preparation, he was not far off the champion Brendon Leigh’s times. His mother thought he should go back to school. But that wasn’t racing.

So, in 2019, he signed on to drive for Renault in the esports series. “Jimmy Broadbent says a great thing,” says Opmeer, referring to the popular sim racing YouTuber. “He says that the driving might not be real, but the racing is. I think that’s very much true.”

In Opmeer’s second season, he won. In his third season, he won. In his sixth, he won. He has not dominated a field like this since he was nine. Opmeer once said that his career has been the reverse of what his current competitors would like to achieve: demonstrate talent in sim racing, then get into the feeder series, and one day Formula 1. (Which is referred to in sim racing circles as “real-life racing.” I ask if Opmeer finds this term at all demeaning. “No,” he says, a little perplexed. “It’s fine.”)

Pretty much everyone in the esports series, Opmeer thinks, would jump over to real-life racing in a heartbeat if they could. Including you? I ask.

“Yeah,” he says. “I would love to.”

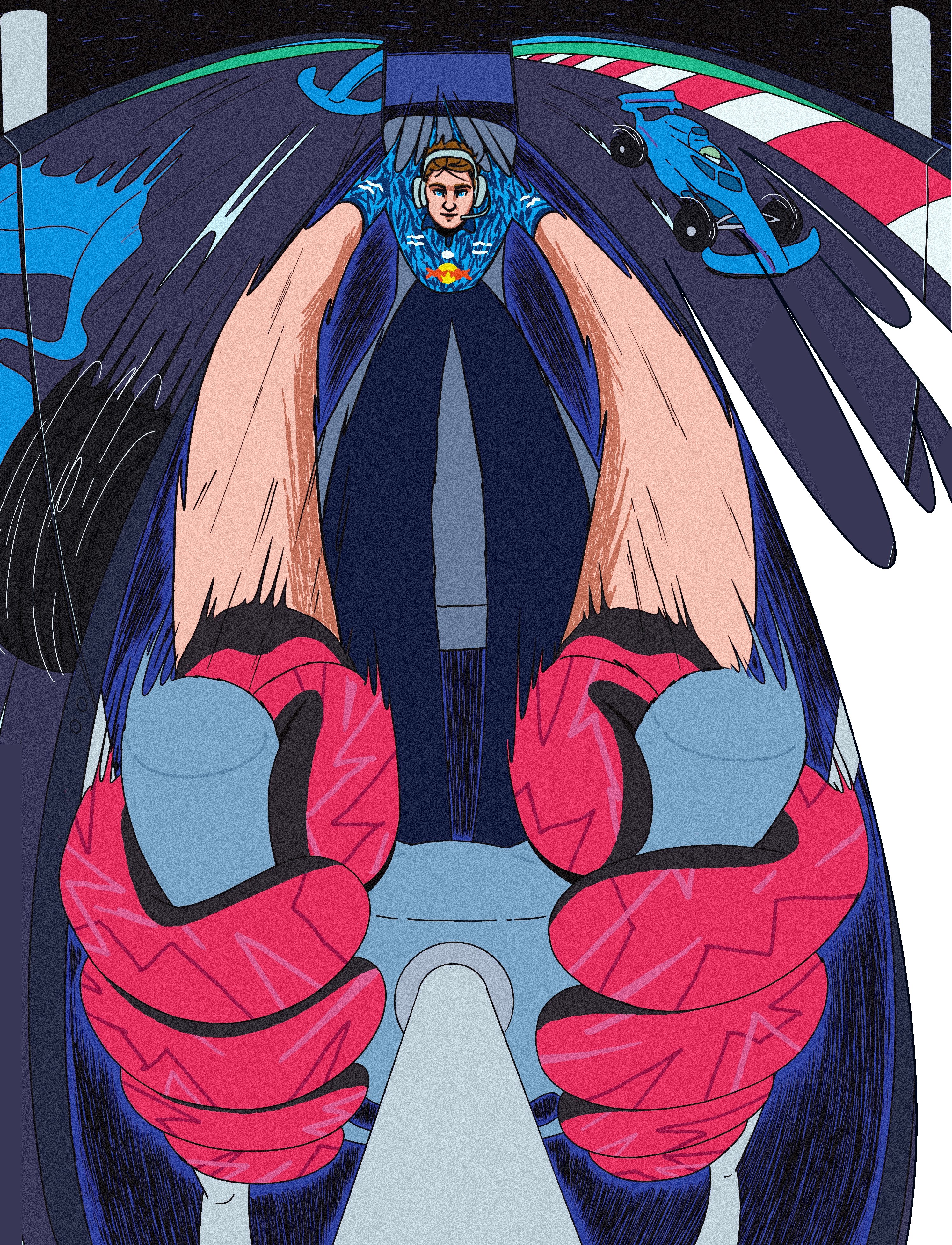

Jarno Opmeer races a sim version of the Dutch Grand Prix in the F1 esports series.

Jarno Opmeer clinches the 2025 F1 Sim Racing Drivers‘ World Championship in Abu Dhabi.

In 30 years, Lando Norris and Oscar Piastri will be modeling Rolexes, investing in F1 teams, and managing the champions of the future. There is little conception of what the life of a professional sim racer looks like at fifty. Johnathan “Fatal1ty” Wendel, a professional Quake and Unreal player, retired at 26 and now, at 44, makes headsets and mousepads.

The smartest thing Opmeer ever did, he says, was to launch his YouTube channel within the week of winning his first championship. Racing goes away in the off-season, but Opmeer doesn’t. He’s always posting. Content creation is a valuabe income stream for Opmeer; it is also a kind of insurance.

“If I’ve got a season where I’m a little bit worse, teams would accept it a little bit more,” he says. “If you’ve got a big reach, it helps them marketing-wise.”

When he was dropped by MP Motorsport in 2017, the only people who followed him on social media were his family and a few friends. Building an online presence has displaced Opmeer’s reliance on sponsorships, which caused him trouble in the past; instead, he has created a currency around his personal brand. If he were, once again, to be dropped by a team, he wouldn’t be left out in the wilderness. He will never again be at the mercy of a bad season like he was at MP Motorsport.

But what will life look like when he leaves the driver’s seat — what will Opmeer actually do?

“If I just do content, I’ll be too bored,” he says. But, the truth is, he’s not sure he can do anything other than race. So, the elder statesman of sim racing will keep chasing podiums as long as they’ll let him. It’s hard to envision what’s next right now, but that might not matter — the last time his career was over he reinvented himself in a field that barely existed.